“I’m being pushed underwater. I lose vision – it goes blurry – and I lose my sense of hearing, so all the sounds merge into one as a jumbled noise.

“I’m being pushed underwater. I lose vision – it goes blurry – and I lose my sense of hearing, so all the sounds merge into one as a jumbled noise.

“I’m still conscious, I’m still standing, but I can’t make sense of anything around me.

“From there, it goes into what I call a hallucinogenic nightmare, where I’m seeing things that make me panic and get stressed, so I end up sweating.

“I’m trapped. I’m trapped underwater with no escape.”

This sounds like an awful nightmare, but for Katie, it’s not a dream at all but a reality. Until recently, Katie used to have seizures and each would elicit those feelings for her. They would leave her exhausted and she would need to sleep for hours after coming round from one.

Seizures are something that every person with epilepsy – one in every 100 of us – has experienced. For some, it may be a regular occurrence.

But epilepsy is still misunderstood, still often undermined, and still feared and discriminated against. It’s often invisible in the political sphere, invisible to policymakers, invisible in the media and invisible to the public. And yet, it is one of the most common neurological conditions in the world, with 630,000 people in the UK living with epilepsy.

In a recent survey of nearly 800 people with epilepsy, nearly two thirds (65%) said their condition is still misunderstood by most.

For someone like Fathiya, who is from Somalia, misconceptions can be even more commonplace. She has had epilepsy for 18 years, and says there is still stigma in her community. She says: “After a seizure, I feel like I’ve been thrown under a bus and [been] ran over by it. I feel exhausted, tired, mentally and physically.

“On top of that, I have to deal with the stigma that comes with epilepsy from my community, because they think I’ve been possessed by the devil, or that epilepsy is highly contagious.”

The survey also revealed that epilepsy affects how people are treated. A third of people said they have been bullied or harassed because of their epilepsy. More than half (57%) of people reported feeling depressed because of their epilepsy, and a third of them even admitted they had thought about taking their own life.

A sinking feeling

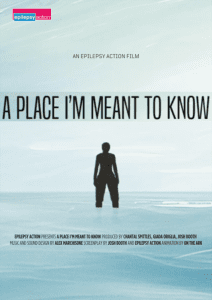

This year, Epilepsy Action is determined to help everyone to really see epilepsy. The organisation has released a powerful short film, A Place I’m Meant To Know, which transports the viewer in the centre of a seizure. This emotive and immersive project is aiming to shake up public perception of the condition.

It asks the world to stop and finally see epilepsy for what it truly is, pushing for a change in attitudes towards it.

A Place I’m Meant To Know was created using real life testimonials from people with epilepsy about exactly what it feels like to have a seizure. They shared visceral descriptions of their experiences, including “you feel very far away”, “going into a dreamlike state”, “a sinking feeling” and “an out-of-sync sensation between the body and the brain”.

The film’s emotive soundtrack, which won Best Soundtrack at the Phare International Film Festival, was composed by musician and producer Alex Marchisone, who has epilepsy. While his epilepsy is now controlled with medication, he remembers vividly what seizures feel like.

He says: “Seizures have just been horrific for me. Aside from the various physical injuries I suffered (including a broken shoulder and various spinal disc fractures and wedging) it’s the sheer number of postictal symptoms that have left a scar. Long periods of ill synaesthesia, impending gloom, strong sensorial confusion.”

Alex first got involved with this project after attending an Epilepsy Action Talk and Support group in London and hearing other people’s experiences. “I remember I saw some real suffering there, and I thought that, amid the ever-noisy communication-driven and social media world we live in, this wasn’t expressed and spoken about.

“I reached out to the wonderful team at Epilepsy Action and after a few talks, we landed on starting this project, which has been nothing short of amazing on both a human and artistic level.”

Deeply gloomy ‘leftovers’

Starting the project, Alex was keen to translate all aspects of seizures into music in an accurate and honest way. He explains: “I wanted to try and convey just how powerful seizures are, and how much they affect the person experiencing them. The music needed to be powerful, as a seizure is, and convey some of the feelings that hardly can be expressed in words: sensorial confusion, synaesthesia and so on.

“I wanted to do something more unexpected, avoiding some of the composing-for-media cliches. All in all, I wanted the piece to be powerful, and I wanted it to convey some of the hard-to-communicate feelings and some of those deeply gloomy ‘leftovers’, while retaining an aspect of ‘beauty’ to the music and a sense of solace for people with epilepsy.

“The music needed to make sense on its own, too, and represent my point of view as a composer and music producer.”

Rebekah Smith, chief executive at Epilepsy Action, says 2025 is the year to bring epilepsy out of the shadows. “We are so proud to be launching ‘A Place I’m Meant to Know’. We’re hoping it will really get people to stop and think about what it feels like to have epilepsy.

“It wants to give a voice to people with epilepsy, helping to visualise and bring to life something they feel but may struggle to put into words for others to understand.

“We often say that epilepsy is the ultimate hidden condition. It very rarely gets mentioned or portrayed in the media, when it does it’s too often in a negative way. What’s more, many people have no idea about it despite it being so common and we still hear too many discrimination stories, day in and day out.

“A new year marks a new beginning for most of us. We want 2025 to be the year epilepsy finally comes out of the shadows. Before we can change attitudes around epilepsy, we need to make it visible. We wanted to do this in an unexpected way, through music, visuals, and the real stories of people with epilepsy.”

Falling in slow motion

Lewis has had tonic-clonic seizures, and wishes people knew more about what it feels like before and after a seizure like that.

He says: “The best way that I can describe a seizure is that you’re looking through a kaleidoscope, where you can see lots of vivid images and patterns. Then you get a similar sensation to when you’ve fallen in your dream, only that is in almost slow motion.

“Having epilepsy takes a big toll on the body, both physically and mentally, particularly when you’re coming round from a seizure, because the brain has essentially had to reset itself.

“And this can lead to other challenges. So, for me, after a seizure, I battle with tiredness, grogginess, and even memory challenges on occasion, which can be quite upsetting.

“And people don’t really see that either, they only see the physical damage from the seizures, if the individual’s cut their tongue or bruised themselves when they’ve fallen.”

Lewis, like many others, wishes that people would take the time to understand more about what having epilepsy is actually like, including the experience of seizures and what it’s like to come round from one, rather than believing the misconceptions.

“I feel like people only see the seizures and assume you’ll be fine when you come round from that,” he says.

“But there’s a lot more to it than that.”