If you would like to talk to someone about epilepsy, our trained advisers are here to help.

What would you like to find out about today?

Other names for self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures (SeLEAS)

Older terms for this syndrome that you may still hear include:

- Panayiotopoulos syndrome

- Early-onset benign occipital epilepsy

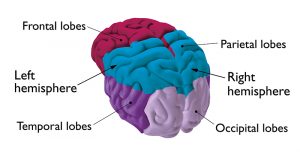

The term ‘occipital’ relates to the area of the brain where the seizures begin. The occipital lobes are responsible for processing what we see (visual information).

‘Occipital’ sounds like this: ok-sip-i-tl

Who gets SeLEAS?

SeLEAS usually affects children between 3 and 6 years. It may also affect children as young as 1, and as old as 14 years, but this is much less common. Some studies have shown around 1 in 20 children with epilepsy between the ages of 1 and 14 have this syndrome. Although, more recent research shows it might be less common than previously thought.

Children with SeLEAS don’t usually have a family history of epilepsy. There isn’t usually any history of problems during birth or development problems. Some children may also have febrile seizures.

Symptoms

Children with SeLEAS get focal seizures. This is a seizure that starts on one side of the brain. The main seizure type in this syndrome is known as an autonomic seizure.

In an autonomic seizure, your child may have the following symptoms.

- Retching and feeling or being sick – often several times

- Becoming very pale, or sometimes looking flushed

- Very large (dilated) pupils

- Changes in heart rate, breathing rate and temperature

- Sweating lots and drooling

- Losing control of their bladder or bowels and accidentally going to the toilet (incontinence)

- Producing tears without crying

When the seizure first begins, your child may become restless, frightened or unusually quiet. They will usually be aware of what’s happening at first, but may become confused and unresponsive during the seizure. As the seizure goes on, your child will often move their eyes and turn their head to one side. They may stay like this for many minutes, or even hours. Often the seizure will end with jerking movements down one, or both sides of the body.

Over two-thirds of seizures in SeLEAS begin during sleep. The seizures can last a long time, often for 30 minutes or more. This can lead to a situation, called ‘non-convulsive status epilepticus’. This is when a non-convulsive seizure lasts for too long. Even after a long severe seizure, the affected child will usually feel normal after a few hours’ sleep.

Rarely, children with SeLEAS get another type of status epilepticus, called ‘convulsive status epilepticus’. This is an emergency situation where you get tonic-clonic seizures one after the other, or lasting a long time. Most children with SeLEAS won’t get this.

Most children with SeLEAS don’t have many seizures. Some children only have one seizure, and most have less than 5 in total. However, a few children may have seizures more often.

Diagnosis of self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures

Your child should see a specialist doctor called a paediatrician for an assessment. They will want to examine your child and ask questions about their symptoms. It can be useful to take a video of your child’s seizures if you’re able to. This may help your child’s doctor to confirm the diagnosis of SeLEAS.

SeLEAS can have similar symptoms to several other conditions. These include other epilepsy syndromes as well as other conditions not related to epilepsy. Your child’s doctor may refer your child to a specialist in children’s epilepsy, called a paediatric neurologist, to make sure of the diagnosis.

Your child will have a test called an EEG (electroencephalogram). The EEG records electrical activity in your child’s brain. If your child has SeLEAS, the EEG often picks up abnormal activity (called spikes) on both sides of the brain. Sometimes the specialist may arrange for your child to have the EEG when they’re asleep, or when they haven’t had much sleep (a ‘sleep-deprived EEG’). This is because abnormal brain activity is more likely to show up on the EEG when your child is tired or asleep.

Your child may also have an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan if the diagnosis is uncertain. But these are usually normal in children with SeLEAS.

Treatment for self-limited epilepsy with autonomic seizures

Many children with SeLEAS don’t need treatment with epilepsy medicine. This is because the seizures don’t happen very often and because most children don’t have them for very long. Taking epilepsy medicines doesn’t make a difference to whether the epilepsy will go away or whether another type of epilepsy might develop later on. Talk to your child’s doctor if you have any concerns about their treatment or care.

Your child’s specialist may recommend treatment with epilepsy medicines if they’re having lots of seizures, especially if this interferes with school and learning.

Sodium valproate can harm an unborn baby if taken during pregnancy. For this reason, if your child is able to get pregnant, or may do when they’re older, your child’s paediatrician will usually suggest an alternative medicine. If they do recommend treatment with sodium valproate, they will discuss the risks and benefits with you and your child first.

Your child’s specialist may also discuss a ‘rescue’ or emergency care plan with you to treat any prolonged or repeated seizures. However, it’s very unlikely that your child will need one, unless they have frequent and prolonged seizures.

Information about epilepsy medicines for children can be found on the Medicines for Children website.

Outlook

Nearly all children will stop having seizures 1 to 2 years after they first start. How long it takes for them to stop isn’t affected by whether or not they have epilepsy medicines or any other treatment. SeLEAS isn’t linked to any development, learning or behaviour problems.

Around 1 in 5 children with SeLEAS go on to develop other epilepsy syndromes as they get older. The most common one is Self-limited epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes (SeLECTS). This is also a syndrome that children tend to grow out of as they get older.

Although SeLEAS isn’t associated with any long-term problems, it can be frightening or upsetting when your child has these seizures, especially if they last a long time. Learning about the syndrome and how to manage seizures can help. Your child’s doctor can support you with this.

Support

Contact – for families with disabled children

Freephone helpline: 0808 808 3555

Email: helpline@contact.org.uk

More epilepsy syndromes

Here to support you

Send us your question

Send a question to our trained epilepsy advisers. (We aim to reply within two working days).